Sarah Moore Grimke

(1792-1873)

Born in South Carolina to slaveholders, Sarah Grimke would become an activist for the emancipation of slaves and campaign openly for women’s rights. As a child, she defied existing law and taught Kitty, a young enslaved girl given as her “constant companion,” how to read, for which she was punished. Learning law and debate along with her brother, her family denied her formal schooling even though her father, a lawyer and later a state supreme court justice remarked she would have been the greatest jurist in the country, if only she were a boy.

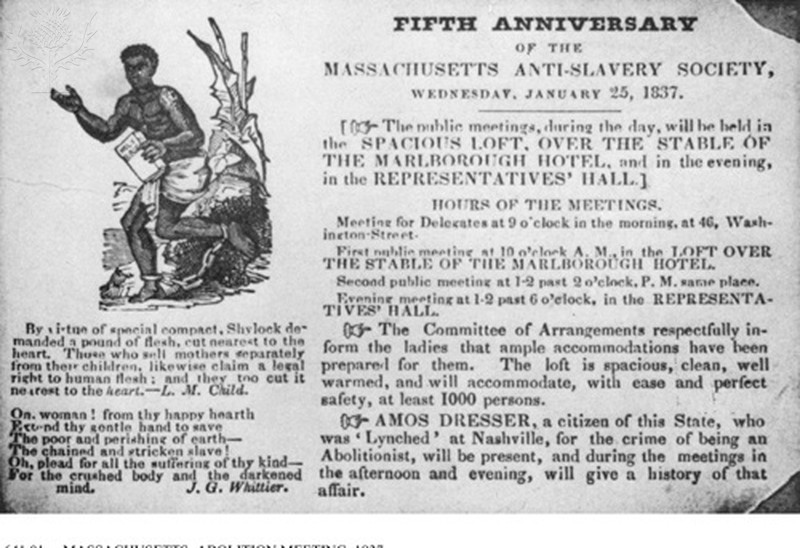

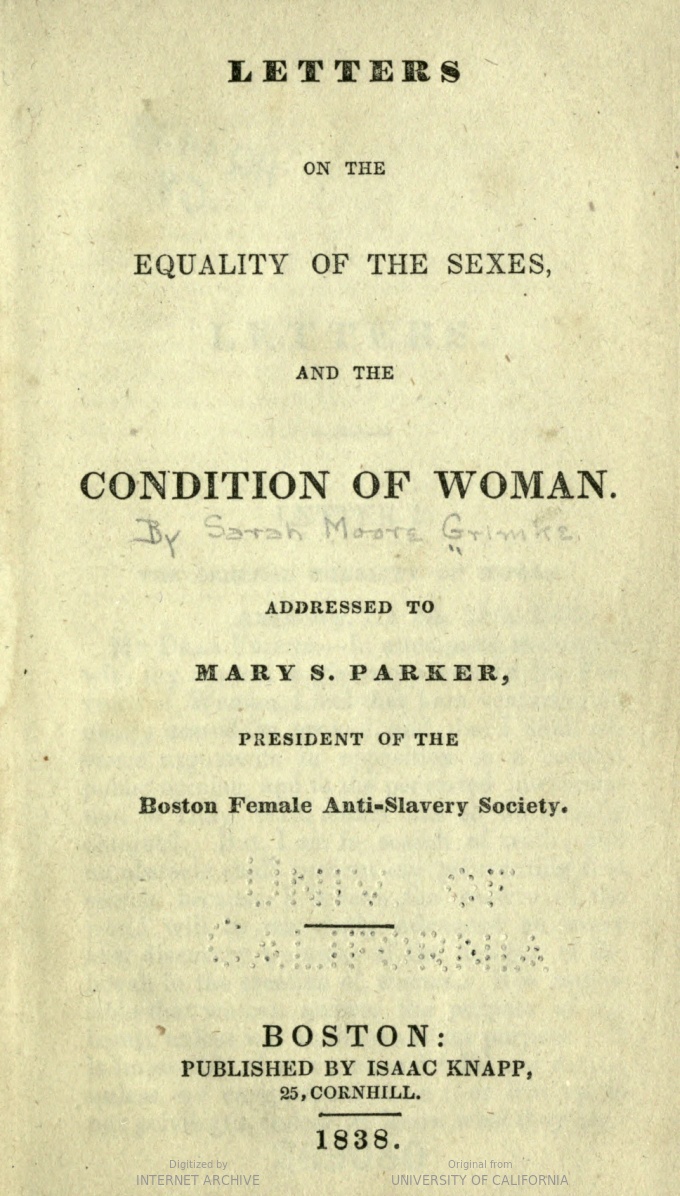

Accompanying her ill father to Philadelphia, Sarah entered life without slavery and discovered the Quaker religion. Some years later she moved permanently to Philadelphia and joined the Quakers, bringing her younger sister Angelina along with her. The sisters joined the Female Anti-Slavery Society founded by Lucretia Mott and after Angelina’s letter describing what they witnessed on the plantation was published in the Abolitionist paper the Liberator, their lives changed. Chastised by the Quakers, unable to return home under threat of arrest, but embraced by abolitionists, the Grimke sisters would speak publicly about abolition and women’s rights throughout the Northeast. Being some of the first women to speak publicly, they shocked many listeners who were surprised that women had the audacity to speak openly on these issues. She came to realize that “to change the status of one group [the slaves] meant changing the status of all.” The sisters wrote a series of anti-slavery pamphlets, including Sarah’s An Epistle to the Clergy of the South (1836), Address to Free Colored Americans (1837), and Letters on the Equality of the Sexes (1838), the first book on women’s rights from an American author. In Letters on the Equality, she would compare the the subjection of women in society to that of slavery.

Due to her campaigning for women’s rights, Sarah was denounced by the church. Abolitionists were also concerned she was splitting attention from slavery for discussing both topics. She stepped away from public speaking for a time, running schools and writing. She continued to campaign for equal rights until her death. At 79, she led a group of women through a blizzard to the local polling place claiming that the Fourteenth Amendment gave all the right to vote (she and the others were not allowed to vote). She inspired others like Elizabeth Cady Stanton to start the women’s rights movement.

“But I ask no favors for my sex. I surrender not our claim to equality. All I ask of our brethren is, that they will take their feet from off our necks, and permit us to stand upright . . .”

-Sarah Grimke

Letters On the Equality of the Sexes, And the Condition of Woman: Addressed to Mary S. Parker.

Learn More

Learn more about Sarah Grimke by reading a fictionalized account of her life or her own words in a collection of her writings.

Works Cited

Duncan, Joyce. "Sarah Moore Grimké (1792–1873)." Shapers of the Great Debate on Women's Rights: A Biographical Dictionary, Greenwood Press, 2008, pp. [13]-17. Shapers of the Great American Debates 9. Gale eBooks,

https://link-gale-com.byui.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/CX3252600015/GVRL?u=byuidaho&sid=GVRL&xid=747c17d3. Accessed 17 July 2020.

Alexander, Kerri Lee. "Sarah Moore Grimké." National Women's History Museum. 2018.

https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/sarah-moore-grimke.

Grimké, Sarah Moore, 1792-1873. Letters On the Equality of the Sexes, And the Condition of Woman: Addressed to Mary S. Parker. Boston: I. Knapp, 1838.

https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t5cc12w9k